Lady Honoria Bellweather’s chief concern, apart from the ever-expanding mildew patch in the east wing of Bellweather Hall, was not to fall in love. Love, after all, was for servants and poets, neither of whom had to maintain a viable bloodline, or tolerate the Dowager Marchioness’s dinner conversation.

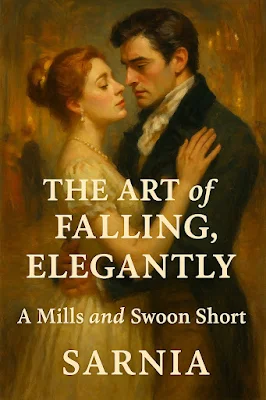

It was therefore particularly inconvenient when, upon entering the ballroom at Carrion House—her gown artfully ruched to imply innocence while aggressively suggesting otherwise, Honoria slipped on a dropped profiterol and landed in the arms of a man who was, by all accounts, thoroughly beneath her.

Major Dominic Arlesford had the kind of reputation that required the use of italics when discussed in polite society. He had been “posted abroad” for reasons that seemed to involve a diplomat’s daughter, a Turkish wrestling match, and a camel with a mild opium addiction. That he was now back in England, glowering by the pianoforte with a scar on his jaw and trousers cut a whisper too tight, was nothing short of a scandal.

“Major,” Honoria said, once she realised he was not going to drop her, “you appear to have caught me.”

“It wasn’t intentional,” he replied. “I usually only catch women when they’re running away.”

“Oh, how droll,” she said, too quickly, and hated herself for it.

Over the coming weeks, Dominic appeared in the strangest of places; at her aunt’s tea mornings, at her cousin’s fencing demonstration, once even in the hedge maze at dusk, which might have seemed accidental if he hadn’t had a blanket, a bottle of something French, and a loaf of bread he was inexplicably slicing with a cavalry dagger.

“Do you often picnic in topiary traps?” she asked.

“Only when I expect company,” he replied, tearing a piece of bread with his teeth like a wolf who owned a cravat.

It was becoming intolerably difficult not to be intrigued by him.

The inevitable scandal occurred, of course, during the annual Harvest Ball, where the wine flowed like minor gossip and everyone’s virtue was at risk by the second quadrille. Honoria, emboldened by three glasses of claret and the knowledge that her corset was on its last hook, found herself whisked onto the terrace by Dominic.

“You’ve been looking at me all evening,” he said.

“I was merely squinting at the lanterns.”

He moved closer. “And last week, at the stables?”

“I was admiring the filly.”

“You said it was gelded.”

“I was being diplomatic.”

Dominic looked down at her, his gaze lingering a moment too long. “You are trouble, Lady Honoria.”

“I assure you, I am merely inconvenient.”

And then, a scandal most decadent. Or at least, a moment so charged that Honoria would later insist the wind had shifted and their lips had merely collided in a freak gust. Either way, a breath was taken, a cravat was tugged, and an earring may have rolled into the shrubbery.

They were discovered by her mother, of course. The Countess of Dorking had the uncanny knack of appearing whenever her daughter’s reputation was most at risk. There was a scream. There was a threat of disinheritance. Dominic was challenged to a duel, but declined on account of his gout (which may or may not have been real).

But by the next Season, Lady Honoria was married.

Not to Dominic—God, no. He eloped with the vicar’s wife and moved to Portugal, where he opened a fencing school for aristocrats who enjoyed wearing tight britches and emitted the the vulgar vanities of men with large endowments.

Honoria married Sir Giles Flapperton, who owned several successful jam factories and, more importantly, a complete indifference to her whereabouts on Tuesday afternoons.

She took up oil painting, eventually. Her teacher, decrepit to avoid any distractions. And, in the privacy of her solarium, she painted an exceptionally lifelike study of the man that may have been or may have not, holding an earring and staring out toward her wherever she happened to be.

THE END.

© 2025 Sarnia de la Mare